If You’re Short on Time…

Key Takeaways:

- Complaints about deer were predominantly based on deer eating residential plants. No natural ecological damage in Mahtomedi was ever studied long-term to determine goals.

- No data showed deer were tested for chronic wasting disease (CWD) or COVID-19.

- The city is not adequately enforcing its deer feeding ban ordinance. Only three code enforcement calls were made in 2021, despite feeders that “were to many to count” and evidence of “piles of several hundred pounds of corn.”

- City resolutions and literature spread misinformation about the relationship between deer, ticks, and Lyme’s disease. Deer are not vectors for Lyme’s disease and are “dead-end hosts.”

- Deer are not managed for biological overpopulation. They are managed to a social aspect. The deer in Mahtomedi are not “overpopulated.”

- The city’s data was incomplete and inconsistent, which makes studying the issue difficult. Data between the city, county police, and Metro Bowhunters showed discrepancies in the number, age, and gender of deer killed.

- The city never documented or knew the legal identities of its volunteer hunters. No background checks were ever required or performed. No data demonstrating the hunters’ credentials or certifications was ever recorded by the city.

- Only 22.5% of the community strongly supported culling the deer by hunting.

- There is no proof that any venison from the hunts was donated to food shelves and charities.

- Despite extensive road work on Trunk Highway 244 and public input at the county level, no wildlife crossing structures are being implemented. These could have consisted of overpasses and underpasses to protect both wildlife and drivers with a 90% reduction in collisions.

- Other mitigation strategies were never considered, including but not limited to: exclusionary fencing, warning signs, changeable and moveable messages boards, motion-sensor warnings, darting and sterilization, reduced speeds, and more frequent clearing of road right-of-ways to improve visibility.

- Conflicts of interest appear to favor hunting over other mitigation strategies, potentially because of the revenue hunting generates for the DNR.

- Mahtomedi failed to implement a sound deer management plan that will be effective over the long-term.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Mahtomedi – A Big City in a Small Town

- The History of the Current Deer Management Plan

- Types of Submitted Written Complaints

- Deer Population in Mahtomedi

- Concern for Ecological Damage

- Concern for Damage to Landscaping

- More on Population Densities

- Chronic Wasting Disease

- Black-legged Ticks and Lyme’s Disease

- Deer Feeding Ban

- Lethal Control

- Metro Bowhunters vs. Other Sharpshooting Alternatives

- Venison Donations

- Migration Patterns

- Relocation

- Vehicle Collisions

- Wildlife Crossing Structures and Fencing

- Sterilization and Birth Control

- Deer Crossing Signs, Other Electronic Mitigation

- Park Remaining Closed to the Public

- Conflicts of Interest

- Recommendations

- What is Mahtomedi missing?

- Conclusion

Introduction: Mahtomedi – A Big City in a Small Town

The Mahtomedi I grew up in is vastly different from the ravaging juggernaut it has become. As a child, I remember running through open fields and exploring the untamed woodlands. I knew neighbors who had troughs to feed the animals, and deer and wildlife were welcomed. (Of course, you can’t and shouldn’t feed deer anymore because of chronic wasting disease.) I don’t remember anyone complaining about flowers being eaten or that there were too many deer. It was exciting and thrilling to see our wooded friends come out to visit, and it seemed that the plants were there for them, not us. People were grateful to live in an area that could coexist with nature.

That mentality has shifted as outsiders move into the city, which was once a quiet small town. I spent a number of my younger years in the Deer Ridge Townhomes. It’s an ironic name now. No deer have been recorded there on Mahtomedi deer survey maps since 2013, except for one lone deer in 2017. Perhaps a solution to the “problem” is to flatten the few remaining nature parcels, which would certainly push out the herd like it did in Deer Ridge.

As people with big city mindsets move in for the educational opportunities and what remains of the “small town” feel, the foundation of what made Mahtomedi special has been continually chipped away until only a gaunt husk of its former untamed beauty will remain, as manicured lawns and fancy ornamentals lay siege on previous native grasslands, woodlands, and wetlands. It’s always interesting to see the complaints from people who purchased land next to Katherine Abbott Park and other wooded acres. You moved next to nature and now expect nature to move… because they’re eating your plants?

I read an article recently about how the author’s family moved from the city to a small town. I wish I could find it again… His father supported development to grow the community and the tax base, and provide for the education system. He considered it necessary growth. Decades later, after all of the trees had been chainsawed, the wildlife had left, and his city was still developing for its tax base, the father admitted to his son that it wasn’t worth it. It reminds me of a letter to the editor where a resident raised issues with unnecessary improvements and governmental conflicts of interest that gave business to its city engineer’s firm. It led to steep assessments for those residents, many concerned they wouldn’t be able to afford it and would have to move. These concerns fell on deaf ears and the city went ahead with its project anyways. The basic message was: if you don’t like it, move out.

Out with the old, in with the new.

It’s a very convenient way to shape public policy by drawing in a target voter base with similar visions while simultaneously pushing out all of the dissenters who liked the community the way it was.

I understand that change is inevitable and that communities evolve and grow. But before I’m inundated with complaints that my perspective is wrong and change is a part of the process… and before I’m smeared again by local papers that fail to print the full story… Look, I do understand some of the concerns with having high numbers of deer in the city. Many of the concerns and the responses to them are frankly misguided at best. There are better ways to address them, and I will outline them in detail below and in subsequent reports.

Considering Mahtomedi surveys consistently show “small town ambiance” to be the most-liked attribute about the city, government leaders should take note about the direction the city is headed, especially since 81% of residents appear to be misguided that the city is protecting the environment “about the right amount.” The “deer problem” is symptomatic of much larger issues at hand.

Kill-only management plans are akin to going to the dentist for a toothache and being asked if you brush regularly. “No, but I own toothpaste.”

The History of the Current Deer Management Plan

The origins of Mahtomedi’s current deer management plan, which utilizes lethal services by volunteer hunters (rather than a strictly sharpshooting program using a qualified contractor) received serious consideration around 2010 with a petition to the city of Mahtomedi. The petitioners were residents in the areas of Trunk Highway 244, Arcwood, Old Wildwood Road, Edgecumbe, Woodland, Salem, and Lincoln Town, citing deer becoming a nuisance by eating various flowers and shrubs. A tertiary reason listed was deer herding, “which can lead to wasting disease.” The petitioners wanted to see the deer population reduced.

It must be stated that Mahtomedi did not appear to have created a deer task force to look at current research to study the problem further. Some of the guiding documents were obtained from other localities’ plans that cited research from more than 20 years before. More recent studies do not appear to have been consulted. However, no studies and guiding information into both lethal and non-lethal control were consulted, with the city attorney responding to the request for such data with, “No data exists.”

The Golden Valley plan from 2006, arguably outdated in terms of the studies it cited, was far more expansive than anything the city of Mahtomedi put together. Golden Valley at least cited research studies to guide their decisions and organized objectives, habitat requirements, population densities, and deer projections. The city of Mahtomedi’s resolution was explicit: remove deer by killing them through hunting. Similarly, a small 2020 petition to the city identified residential plant damage as a primary factor in seeking the deer population “thinned.” All other aspects of deer management seemed to be tertiary and of lesser importance, if even considered at all. More on what research showed will be covered in the following sections.

In fact, Scott Neilson, the city administrator, said in June 2020 that aside from the couple of residents that came the previous fall, he rarely received complaint calls. This was during a presentation by Metro Bowhunters to allow hunting within the city limits. Unfortunately, SCC does not have a video of this meeting to provide for further context.

After the 2020 hunt, Bob Goebel, Mahtomedi’s public works director, noted “half a dozen or more calls from the public,” mainly concerned neighbors during the 2020 hunt on the narrow parcel shared between Mahtomedi and Birchwood. The concerned residents didn’t want anyone on their property. One individual was “quite concerned” to know how many deer were killed and called public works each day for an update. He noted there were “a few challenges to overcome during the weekend” without citing any further information about those challenges, calling MBRB “phenomenal.”

According to the April 6, 2021 council meeting, the 2021 city-wide survey of 400 random residents showed that 15% of residents surveyed felt the deer problem was “very serious” and 30% saw it as “a somewhat serious issue.” Of those 45%, 50% felt it was a good idea and strongly agreed to have a city controlled deer hunt. (This allocation is not clear on the survey but was explained by Goebel during a meeting. The survey makes it appear that 50% of all respondents supported a city hunt.) Only 22.5% of the community strongly favored hunting, yet the city pursued this as its primary deer management solution, hoping that the few public comments provided would “thin out the herd.” Further minutes from the September 15, 2021 Mahtomedi Parks Commission meeting showed that “Vice Chair Costello stated that the deer [were] only passing through and Chair Lindberg stated that there [were] lots of coyotes around.”

I wanted to know more about the planning and contracting of the hunts and filed a data practices request with the city.

Types of Submitted Written Complaints

Like change-driving mechanisms in social policy, public pressure to address the deer population was at the heart of Mahtomedi adopting a kill program to manage its deer.

| Year | Total number of complainants | Eating Plants, Flowers, Shrubs, etc. | Disease Spread/Chronic Wasting Disease/Herding/Overcrowding | Vehicle Collisions/ Other Accidents/ Property Damage | Lyme’s Disease/Ticks | Herd Size/Increased Sightings/No Natural Predators/Saw a Deer | More Deer Increases Predators/Threat to Family or Pets | Feces | Natural Ecological Damage | Wants Deer Meat | Other (Wants hunters, smell of dead deer, harm to deer, no reason stated) | Wants to Hunt/Establish Hunting |

| 2010 | 43** | 43 | 43 | |||||||||

| 2011 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2019 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2020 | 25** | 24 | 1 | 19 | 19 | 22 | 2 | 19 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2021 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||

*Data compiled shows disaggregated tallies of all individual reasons listed for wanting to reduce the deer population. These are not indicative of the total number of complaints, as some correspondences listed several points. Multiple complaints from the same persons within a given year have been merged into one count.

**A 2010 petition had 43 signatures, and 2020 had 18.

Several other correspondences cited wanting the city to use their property for the hunts. One undated voicemail to the city cited wanting hunters on her property because of the high deer numbers. A few other communications wanted more information about the hunts and/or if their properties could be included, without citing reasons. A small number of residents told the city to leave the deer population alone.

It is important to note that this table is only representative of data the city provided for inspection and does not take into account any verbal complaints or complaints during public comment. This table is a best attempt at showing citizen concerns based on public data. City data alluded to a list of complaints that city staff were maintaining. This list was never provided for inspection beyond the original written submissions and city minutes. How these concerns and complaints were being tallied by the city was not forthcoming, but would provide greater insight into the city’s decisions regarding these matters. Furthermore, pursuant to MINN. STAT. § 13.601, SUBD. 2, communications between individuals and elected officials are private, but elected officials can choose to make these communications public, which it appears they may have determined not to. Given the lack of a universal reporting system, the public might never know the extent of the complaints leading to the current deer management program nor the nature of those complaints. This transparency and records management issue is extremely disappointing, as it creates a substantial limitation in studying community input further.

I would hope the city would address the organization and management of its data in the future. (I collated the tables above from available data; these visual representations were not provided through the city.) How can city officials make informed decisions to carry out government functions without having data in an easily accessible format for cross comparisons?

Deer Population in Mahtomedi

It’s difficult to make clear correlations in the data because Mahtomedi did not conduct a deer survey in 2020–the same year the city implemented its bowhunting management plan and the year after its 2019 survey showed only 16 deer, partly due to melting snow. Likewise, Birchwood had no census of the deer in 2020. Mahtomedi’s 2020 hunt, sponsored by Birchwood, resulted in four deer being taken out of the population. The 2021 population in March was at 99 deer. Subsequently, hunters killed 28 deer during six different dates in the fall.

| Year | Total Population | Reported Dead Deer* | Total Hunted | Static # of Remaining Surveyed Deer | # with Hunted | % of Total Population Reported Deceased | % with Hunted |

| 2011 | 111 | No Data | N/A | No Data | No data |

| 2012 | 34 | 9 | N/A | 25 | 26.5% |

| 2013 | 77** | 9 | N/A | 68 | 11.7% |

| 2014 | 107 | 17 | N/A | 90 | 15.9% |

| 2015 | 120 | 19 | N/A | 101 | 15.8% |

| 2016 | 99 | 14 | N/A | 85 | 14.1% |

| 2017 | 73 | 9 | N/A | 64 | 12.3% |

| 2018 | 102 | 6 | N/A | 96 | 5% |

| 2019 | 16*** | 11 | N/A | 5*** | 68.8%*** |

| 2020 | No Data | 18 | 4 | No Data | No Data |

| 2021 | 99 | 10**** | 28 | 89 | 61**** | 10.1% | 38.4% |

| 2022 | 117 | 8 (as of 7/9) |

*not all reports of dead deer were related to wildlife-vehicle conflicts

**official city study graphs incorrectly reported 67 deer. 77 deer are visible on the deer survey map.

***difficult to see deer

****some reported dead deer numbers reported by the city differ from incident statistics from Washington County Police, specifically around the time of the November 2021 bowhunting dates. See the sheriff’s queried log of animal complaints. Additional data from 2022 continued to demonstrate inconsistencies between police data and city data (this discrepancy has been accounted for in the chart above for 2022).

For more information, see the log of dead deer and 2022 sheriff’s queries. It is interesting to note five deer hit within one week–the only logged dead deer by the city in 2022.

Data above does not indicate a circumstantial correlation between deer population and reported deaths. In 2012, when populations were low, the number killed was about the same as four other years. When expressed as a percentage of the total population, 2012 had the highest rate of incidence outside of 2019, which likely did not report an accurate deer flyover count for that year. Interestingly, data for 2018 and 2021 had both lower rates of reported mortality and lower death totals expressed as an overall percentage. Almost 40% of the surveyed herd in 2021 was removed either through hunting, or by accidents and other reported reasons. Despite the loss of at least 38 deer, 2022 survey numbers showed an 18% increase in deer population from the previous year’s survey. The population of the remaining surviving deer from the 2021 survey almost doubled by 2022, which was the second highest reported population count over the decade that data was collected and maintained.

The final summary report of the 2021 hunt showed that of the 20 of the 28 deer killed (or 71%) were does (eight being bucks). It is important to note the discrepancy between this public, government report and the report maintained by the hunting group. Metro Bowhunters’ statistics list that 24 does were taken, six that were fawn does and 18 that were adults. The city’s report shows 17 adult does and that only three fawn does were taken. Which data set is correct? If the city’s report is correct, the hunters will have underreported 14% of the adult bucks that were slain during the 2021 hunt on their official website. The inconsistencies in data are a severely limiting factor for studying this issue and also present other ethical challenges.

Were these underreported by the hunters to lessen the public perception of “trophy hunting?”

Concern for Ecological Damage

Outside of DNR provided resources, there was no little evidence presented to the city about damage from deer naturally occurring vegetation. One citizen expressed concern for natural ecological damage. Remaining data was tallied from being listed as an influence in a sign petition the same year. Few residents expressed individual concern with ecological habitats. Rather, in almost all cases, the primary concern was deer eating residential plantings–not natural destruction. Regarding the request for official survey results for deer damage to vegetation in natural areas, I was informed that no data existed.

Ideal deer density ranges appeared to be based on DNR presentations that cited an ideal goal of 10-20 deer per square mile. However, these “ideal” goals vary widely from place to place and from purpose to purpose. With this, it is important to remember that the DNR’s purpose is not just to protect natural resources, but also to provide hunting and fishing opportunities. The DNR acts to balance these opposing interests in a way that provides opportunities for everyone.

Despite marginal concern from residents over damage to natural habitats, it does not appear that the city researched this topic further. There was little data available from the city to show that the city thoroughly researched specific effects deer would have on our community. There was no data showing the city had studied the deer’s previous effect on or destruction of natural flora, specific species that were being effected, nor goals or projection totals for the types of natural vegetation and wildlife the city would like to see preserved through such deer removal methods.

Yet, the city’s resolution to adopt a management plan said that deer “further disrupt the ecosystem of the City.” By all regards, people disrupt the ecosystem of the city, but I have not seen any evidence that the city is taking measures to slow our impact on our wildlife community or to reverse the massive development. Rather, the city continues to focus on expanding its tax base through new development opportunities.

Much of the concern expressed by the city to the DNR was about implementing a hunting plan. This corresponds with Bob Goebel’s comments in the “Lethal Control” section of this article. Over the course of a decade, most of the correspondences sought to implement hunting within the city and failed to examine all other mitigation techniques.

One citizen wrote to the city that the deer were “preventing any natural forest regeneration by their over browsing of everything,” citing Katherine Abbott Park as an example. However, this comment failed to accurately address the clearcutting and manicuring of paths that have occurred in the park for more than a decade. Certainly, these activities contributed to creating a more ideal habitat for deer.

More importantly, it appears that increased deer presence in Mahtomedi could be due to a number of variables. Suburban areas provide a landscape that is more attractive to white-tailed deer. In the last 30 years, Mahtomedi has experienced rapid growth and expansion, most notably in its clearcutting behaviors. Developments moved in and dense tree canopies were reduced substantially. For those who don’t remember, Mahtomedi used to have large parcels of pine trees planted in rows. Madeline Bodin for Northern Woodlands wrote: “In a forest with even-aged trees and an overstory that lets in no light, it may be the tree canopy that’s suppressing the seedling growth. One study found only subtle differences in a deer-free, full-canopy forest plot.” Bodin has also written about the disappearance of salamanders as a “red flag of habitat harm when humans move in.” Bodin’s article documented comments from Thomas Rawinski, a botanist with the U.S. Forest Service, who noted: “…the criterion that tops all others is the cultural carrying capacity: the number of deer that people are happy having around.”

A 10-year old patch cut in Pennsylvania shows the difference between 10 deer per square mile and 64 deer per square mile. However, in the photograph, it is noticeable that while the patch cut had poor growth regeneration, the surrounding forest canopy did not. If anything, this serves as an indictment of human actions that begin the problem. Surely without any intervention on areas marked for regrowth, deer will munch on the new clearcuttings because those are a preferred habitat. It is also notable that many experiments rely on fencing in animals, which is not an effective predictive model when considering species that will migrate to find more abundant food sources over several generations.

“It is humans who are at the root of our deer problems, not nature.”

Madeline Bodin

According to Steeve D. Côté (2004), few studies have experimentally manipulated deer densities. One study that is frequently referenced relates to deer abundance and its effect on songbird diversity. Notably, songbirds are sensitive to changes in environment. Other changes include the presence of new dominant species, such as white spruce in place of balsam fir, Norway spruce instead of birch, sugar maple instead of eastern hemlock, black cherry instead of mixed hardwoods, savanna systems replacing oak, and hardwoods and Norway spruce replacing Scots pine. But what about changes to the understory reducing habitats for other animals? The study identified about a one-third decrease in intermediate nesters’ richness and abundance. No effect on ground nor canopy nesters was found. Because this is an older study, it is worth noting that more research has been conducted, but that other literature also differs in findings. Other studies discuss finding decreases in vole abundance and increases in white-footed mice.

Many discuss the need for deer removal, which tends to be a frequently used option. Silviculture research discusses strategies to help with plant succession in areas of deer browsing. Newer research also suggests that deer are not to blame for all the problems in forest management, according to the Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Concern for Damage to Landscaping

What appears to be the primary concern in Mahtomedi is deer eating plants, specifically hostas (which are not native to North America), flowers, and other preferred plantings. An easy solution would be for residents to plant deer-resistant varieties that the deer are not attracted to. Another recommendation is to plant more trees and have less lawns in suburban developments. Other affordable mitigation options are fencing in plants and hanging Irish Spring soap at nose-level.

I’m not going to devote much time to this item because this seems to be one of the most human-influenced decisions. People will either mitigate and plant other varieties, or they will continue to plant according to their preferences.

Plant native varieties.

More on Population Densities

It is important to note a distinction in terminology. The media and government officials have irresponsibly called high deer numbers “overpopulation.” Higher numbers of deer are frequently cited in literature as “overabundance.” The deer in Mahtomedi are not overpopulated, or we would notice more profound impacts on their abilities to survive and reproduce. If anything, the habitat appears optimal for them to thrive.

The above terms seem to correlate with biological carrying capacity and social/cultural carrying capacity. The following below is borrowed from The Humane Society’s deer conflict management plan to provide context into biological and social/cultural carrying capacities:

Biological carrying capacity (BCC) is the number of deer a given piece of land (or ecosystem) can support. If BCC is exceeded, that means there’s not enough food for all and some deer will starve. Except in the most extreme and prolonged winters, adult deer rarely starve in suburbs; before deer populations reach that point, fawn production and survival drop off. However, the term is often misapplied. You may hear that “BCC has been exceeded” because people see localized signs of heavy browsing. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that the deer are in critical condition – or that they are anywhere near exceeding their biological carrying capacity. It may just mean that they are eating certain kinds of plants more heavily than others. Likewise, you may hear that 25 deer per square mile (or another number) is what your community “should have.” This one-size-fits-all recommendation is a political judgment that has nothing to do with biology. Depending on the type and quality of food and cover, different kinds of habitats can support different numbers of deer –there’s no one magical number that any community “should” have.

Cultural carrying capacity is the number of deer that is desired or tolerated by people in a given community. Yet this concept is impossible to define because no one level of deer will satisfy all residents. For a gardener, 2 deer may be too many, yet for a nature lover or hunter, 25 deer might be welcome. Surveys show us that people tend to assume that wildlife numbers are parallel with conflict occurrence and severity. That is, people’s desires for more or fewer deer are dependent on whether they’re experiencing conflicts, and the severity of those conflicts. If the conflict is resolved without removing deer, their tolerance level goes up and they perceive there to be fewer deer, even if the number of deer remains exactly the same. Community leaders need to be aware of this phenomenon, and be careful to focus programs on reducing wildlife conflicts, rather than overly focusing on wild animal numbers.

Biological carrying capacity is defined as the “maximum population of a particular species that a given area of habitat can support over a given period of time.” The DNR does not manage deer populations at biological carrying capacities, for obvious reasons. Using this figure, the DNR would prefer to manage deer at “reasonable carrying capacities,” which are defined as: “attempts to maintain reasonable deer populations (densities) that are low enough to ensure productive deer herds and to minimize damage to habitats and other human interests, yet are still high enough to produce enough deer to satisfy hunters.” This seems to balance “social carrying capacity” with the biological carrying capacity. Though, one should be reminded that social carrying capacity strongly relates to peoples’ tolerances of deer populations. Thus, it would seem the “deer issue” in Mahtomedi is more strongly related to peoples’ perceptions than as an actual ecological emergency. It is difficult to know more about this perception in the absence of city survey results in previous years.

As Scott Noland of the DNR told community members, social limits are set through community feedback and social acceptance rather than biological carrying capacity. “We don’t manage deer to the carrying capacity. It’s managed to a social aspect.”

Research provided to the city from Golden Valley’s plan showed that grazing from lower deer densities (13 to 26 per square mile) had little effect on species of woodland flowers. It wasn’t until reaching 65 deer per square mile that the plant could not recover. Regarding the effect of deer on songbird numbers, the deer density threshold was 20 to 38 deer per square mile. The guiding research noted that overpopulation of deer can produce an alteration of the vegetation and wildlife community gradually, and that people may not notice this change has occurred.

Some examples acceptable deer densities:

- 100 deer per square mile of deer habitat in the George Reserve in southern Michigan.

- Cape Girardeau in Missouri showed the “optimal” number of deer per square mile was 20, the social carrying capacity was 40, and the biological carrying capacity was 60. The population there was 37 deer per square mile, which indicated “the local deer population [was] healthy.”

- 30-35 per square mile in Georgia, according to DNR biologist Dan McGowan.

- Between 50 to 75 per square mile in Fairfax City, Virginia “was lower than areas considered to have a deer crisis.”

- Green Bay, Wisconsin recommended a target limit of 25 deer per square mile.

- 32 per square mile could be considered “understocked” in Oklahoma.

- Cayuga Heights, New York recommended 15-20 per square mile.

Most notably, the Wisconsin DNR made the statement that:

“The number of deer that a community wants is a community decision. There is no biologically correct number. The biological carrying capacity of many of our urban areas can be over 100 deer per square mile.”

Wisconsin DNR

This does not refute that clear ecological changes will occur within species’ populations. That makeup is likely to change, as populations will change in a given ecosystem when a species experiences a growth or decline. All factors are interrelated. Deer can and do contribute to population imbalances, but at the heart of it, human actions appear to have some of the most profound impacts on biodiversity.

Recent research by Brice Hanberry, of the USDA Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station and Marc Abrams, from Pennsylvania State University found that deer are not the main culprits of forest decline. As Zoe Clemons of the Rocky Mountain Research Station wrote: “Researchers found white-tail deer have not reduced tree densities at landscape scales across the Eastern U.S. In fact, they propose other management influences and fire exclusion have had bigger impacts. This research prompts us to ask new questions about hunting management and forest wildlife habitats.” Suburban areas also seem to regenerate more quickly than forests with deer (and can regenerate at higher densities).

Mahtomedi appears to be blaming the deer for a problem it started more than two decades ago. If ecological imbalance was a cause for implementing a deer reduction plan, any data should exist within the city to longitudinally document changes in habitat for long-term studying. No such specific data exists beyond a series of residential complaints–at least, there was no responsive data provided to my data practices request to study this issue.

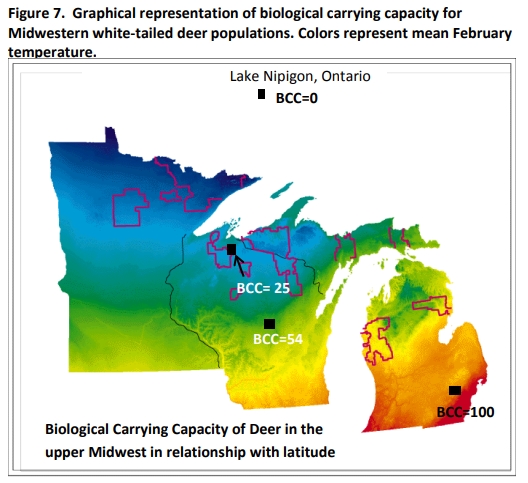

The graphic below, taken from the Minnesota Deer Population Goal Setting

Team Information Packet, shows that regions similar to Mahtomedi’s climate would likely have a biological carrying capacity just below 54.

The DNR’s position is that “Management for RCC attempts to maintain reasonable deer populations (densities) that are low enough to ensure productive deer herds and to minimize damage to habitats and other human interests, yet are still high enough to produce enough deer to satisfy hunters.”

The DNR further stated: “Due to a desire for increased hunting opportunities, some 2015 Deer Advisory Teams advocated for historically higher deer densities in some areas, for example, 18 to 24 deer per square mile in DPA 183.” Other areas of the state were concerned with dwindling deer numbers, which have affected their opportunities to hunt. Could it be that the DNR is answering these grumblings with suburban hunts in their place? If concern for species survival and biological diversity was at the heart of this argument, the DNR would not have designated 20 to 25 deer per square mile in DPAs 249 and 258 in 2015–which appears to be in close relationship to the actual biological carrying capacity of 25.

“The amount of food and cover available for each deer will decrease as deer numbers increase toward BCC and, as a result, the number of fawns recruited per doe will decrease. When food resources are limited, physical condition and adult deer survival also declines. Deer in poor physical condition will have lower body weights and bucks (particularly yearling males) will possess antlers with fewer points and smaller beam diameters. …When a population is at BCC there is no harvestable surplus and any additional mortality (harvest), by definition, reduces the population.”

It would seem that high population numbers tend to correct themselves.

The report furthers that, “Research indicates that many deer hunters would advocate for a population that is about 50% of BCC as this is where the highest sustainable annual harvest could be taken.” Coincidentally, Mahtomedi’s deer population has historically fallen into this range. Even if it were at density levels higher than recommended, Mahtomedi’s deer population still falls substantially below the defined biological carrying capacity, at times falling within the “moderate-low” and at other times “moderate-high” reasonable carrying capacities. At the high end, there would be some change to natural composition, especially concerning susceptible plants. At the lower, only moderate changes occur to the most susceptible species.

Successful management is managing deer conflicts, not numbers.

The Humane Society of the United States

Again, this appears to be more of an issue within the community regarding their flowers rather than the actual ecological changes. If the city cared more about these changes, there would be substantially more evidence of work to care for and preserve existing areas of natural diversity. In my 30 years, I have personally witnessed this decline within city values. At the time of this publication, a developer proposed an apartment complex at the location of the Lakeside Club which would remove 16 of the existing significant 18 trees, replacing them with “overstory and ornamental[s].” The site for this 39-unit development abuts natural wetlands. Certainly these human actions contribute strongly to the decline in biodiversity, as well as contribute to the “deer problem” as urban sprawl and edge landscaping continues to significantly alter natural habitats.

Studies show the effects of clearcutting on deer browsing. It seems more of an indictment of city forestry management practices and expansive development than a shot at the deer. Suburbanization and continued development to expand the city’s tax base are likely to further impact the natural ecosystem in profound and permanent ways. Because most residential-zoned buildable lots have been filled, the city will likely continue to expand into multi-level apartment complexes that do not fit the traditional landscape nor the historical norms of the city. Is there any concern for our native wildlife and protected wetlands? We like to scapegoat nature for problems we started. Once the damage is done, the effects could be irreversible for decades, if not forever.

Regarding reproduction, the guiding research did not study fawn survival rates. However, other research also suggests a low survival rate of fawns–about 45% according to one study. Other studies also note the same findings. This would suggest that lack of predators in suburban environments might not substantially alter the speed at which deer are able to repopulate. It seems that the buck-to-doe ratio is important to the total number of new offspring the following season. Much literature has been devoted to the study of controlling bucks and does, survival rates of fawns, and other contributing factors to population growth. In some areas of the country, constituents are battling the exact opposite problem: trying to increase deer numbers.

This is part of the problem with projecting deer populations into the future. The city’s data often lacks enough detail to know the approximate age and gender of dead deer that have been logged by the city. Furthermore, inaccurate kill reports–either by Mahtomedi or by Metro Bowhunters–presents a further problem.

The Humane Society posits that, “What we want to see in the natural world is influenced by our aesthetic preferences—which may not be grounded in any biological reality. It’s vital that community leaders have baseline data collected so that deer impacts can be measured, and make sure any action plan is tailored to achieving very defined and realistic goals which can be reliably assessed.”

Chronic Wasting Disease

Chronic wasting disease was listed as a major concern for residents in 2010. Not a single deer killed during the city’s hunts was ever reported to be tested, nor were any CWD test results required nor submitted to the city. Dan Christensen of Metro Bowhunters previously informed residents that, “We don’t have a mandatory program of our own. There is no mandatory testing in this area for CWD.” Thankfully, it appears the DNR is requiring mandatory testing in select areas this upcoming year. This is a practice that should be mandated statewide for every deer taken in an effort to proactively get ahead of the spread of chronic wasting disease. Early detection is key since deer can harbor the prion disease for more than a year before showing any symptoms.

Prions of CWD have been found to be infectious in the environment for at least two years, also binding themselves to different soil substrates and increasing their infectious potential. After talking with the DNR, I discovered that prions have been infectious in soil for at least 16 years. This pertains to scrapie in sheep, a proposed origin of CWD in deer. University of Minnesota fact sheets also confirm that prions have persisted for this duration after power washing, chlorine treatment, and sodium hypochlorite to decontaminate.

The exchange of captive deer is the primary source of spreading this terrible disease. Arguably, the practice of farming trophy animals for big game hunts may contribute primarily, if not exclusively, to wild herds from captive deer. Approximately 13% of Wisconsin deer farms are registered as CWD-positive. To further the concern, deer from these farms have been transferred to Minnesota. This is an exceptional problem given that symptoms usually do not show up for 18-24 months. By that point, infected deer that have incubated CWD have been introduced to and lived in close proximity with the captive deer herds.

As featured in the StarTribune:

It’s shooting fish in a barrel–not sportsmanship. Essentially, the demand to hang a large rack on the wall is at the root of much CWD spread. Illegal farming practices have also contributed to the spread of the disease through illegal dumping of carcasses and lax treatment by their overseeing regulatory agencies. In short, deer populations are in danger because of an exclusive, niche market. Deer farms make approximately $5,000 for smaller deer and over $15,000 for larger specimens.

For those who are worried about CWD, the real solution might be to ban the practice of deer farming, except in circumstances surrounding research and preservation. For any farms that are allowed to operate, the transfer of deer should be strictly prohibited.

For more information about chronic wasting disease in Minnesota, including testing data, the Minnesota DNR provides a toolkit on its website for its management history. In 2021, CWD inched its way into our neighboring Dakota County. Of the deer recorded with CWD since 2010, 62% were identified because of hunter testing, whereas 28% were identified through DNR culling. The DNR reported 184,698 deer hunted in the 2021 season and 197,315 deer in 2020, which is close to the 183,062 reported in last year’s just-concluded statistics count (which was last updated on January 11, 2022). It is important to note that the data does not include deer harvested during special hunts, such as programs implemented by Mahtomedi and the metro area. (See deer reports and statistics for more information.) CWD statistics are measured from July through June. Hunter harvested deer make up a significant chunk of the positively identified cases. Only 15,536 tests were administered in the 2020-2021 season. There were 18,571 tests in the 2019-2020 season.

Zone 701, which is the metro area, does modestly better. In 2021, 2,331 deer were harvested (though this number does not include deer harvested by special hunts). Only 408 deer were sampled for CWD. Of those, 168 were hunter harvested and 228 were by shooting permit. The previous year was bleaker. In 2020, only 2,623 deer were harvested (again, not including special hunts). Of these, only a meager 223 were tested for CWD (97 by hunter harvest and 107 by shooting permit).

Essentially, only 8.4 deer out of every 100 killed are tested for CWD. Granted, the math is a little fuzzy since deer culled are not included in harvest totals and the percentage could be even lower, but this provides a close approximation of just how few deer are tested. When hunters bag almost two-thirds of positively identified cases (not counting another quarter identified through culling), the data is clear. Hunters must start testing all kills to provide the maximum amount of data to slow the spread of CWD in Minnesota. I do not believe that Minnesota is doing enough to require testing and data when only a small percentage of deer are tested. At the very least, the city of Mahtomedi should require testing to do its due diligence as the map of affected areas continues to edge in.

Black-legged Ticks and Lyme’s Disease

The city of Mahtomedi’s deer management plan states: “High deer populations also lead to issues such as increased potential for Lyme disease.” City literature even states: “The high deer density also causes… an increased potential for contact with deer ticks that could result in contracting Lyme disease.” However, there’s a problem with this statement: it’s exceptionally misleading.

Information that guided the city’s deer management plan even refutes this: “Although Lyme disease needs to be taken seriously as a health issue, there have been no direct links made between deer population densities and the potential risk for Lyme disease.” Scott Noland of the Minnesota DNR told people at a local meeting that, “Deer aren’t the end-all for Lyme’s disease.” Dropping the deer population, he said, “You’re still going to have the possibility of Lyme’s within the landscape.” Ticks typically only feed once during each stage and then fall off their hosts once engorged. This means it is highly unlikely that a tick that has just gotten a meal from a deer host will reattach to a human.

And science refutes the notion that killing deer will substantially decrease the risk of Lyme’s disease. Local residents appeared surprised by this statement, yet this red herring still persists in the community. A public education campaign would more appropriately dispel these myths.

Ticks do not contract Lyme’s disease from deer. Rather, the primary vector of transmission to ticks is from the white-footed mouse. According to the faculty of mathematics and natural sciences at the University of Oslo, “Ticks are born pure.” Other sources concur that ticks are born free of pathogens and acquire them through their hosts. Because of this, the source of a tick’s first blood meal while in its larval stage will determine the diseases carried to its second and third meals. During its larval stage, ticks’ primary sources of feeding are rodents and birds.

Transmission of disease is most likely in the tick’s second stage of development, the nymph. Increased odds of transmission to humans are possible because of the lack of detection due to the nymph’s small size. It is improbable that the tick has ever feasted on a deer at this stage of its life cycle. Deer, humans, and other mammals are necessary for the tick to complete its second and third stages. By its adult stage, ticks are typically large enough to be detected and removed from skin before disease transmission can occur. The transmission of Lyme’s disease from ticks to their hosts typically takes 36-48 hours, according to the CDC. Often, ticks are detected prior to this and removed. (Scientists are also working on gene-editing techniques that would boost ticks’ immune systems, thus keeping ticks clean of the bacteria that causes Lyme’s disease.)

According to the Pennsylvania Game Commission, deer are a “dead-end host” for Lyme bacteria, stating that they do not contract nor spread Lyme’s disease. This finding is consistent with other sources, from The Humane Society to Harvard University. According to The Humane Society of the United States: “Even when the deer population is reduced by as much as 86 percent or to as low as nine deer per square mile—tick numbers do not decline enough to reduce tick reproduction or human disease.” Tamara Awerbuch-Friedlander–an expert in Lyme’s disease, public health scientist, and professor at Harvard University–noted that removing deer does not decrease the tick population. It just increases the number of ticks feeding on each deer. If eight or fewer deer remain in a stretch of 5.5 miles, ticks will decrease very slowly over time. Complete eradication of the deer population is necessary for the possibility to decrease the tick population over many years. Even so, ticks are a multi-host organism. Removing only one of its hosts will lead to parasitism of alternative hosts and congregating on other species in higher numbers. The few valid arguments that do appear to have some scientific backing are that ticks can hitchhike on deer and travel to other areas and that deer are a host that allows ticks to complete their life cycles. But so can other animals. Birds also contribute to ticks’ movement to new areas. I’m an avid gardener, and I’m not afraid to admit I’ve unknowingly transported ticks 35 miles away with me to work on several occasions.

Additionally, drawing conclusions about the correlation between tick populations and deer populations can be misleading. For the most part, tick populations oscillate irrespective of the number of deer, fluctuating between high and low points due to various other factors such as climate, seasons, weather, temperature, and rainfall. Kugelar et al. (2016) found “evidence linking deer reduction to reduced human Lyme disease risk is lacking.” The team furthered that, “Robust, reproducible scientific evidence should support any recommended public health intervention, let alone one that is both costly and controversial.”

It would be my recommendation that the city modify its discriminatory language (“deer” tick) to better align with CDC classification (black-legged tick) and to dispense with the spread of misinformation that deer significantly contribute to the spread of Lyme’s disease. I don’t see any city literature being published to warn citizens of the dangers of white-footed mice nor city-wide strategies to stem their predominant involvement in the transmission of Lyme’s disease. It would also be effective to promote and implement 4-Poster bait box systems for deer, and also Damminix Tick Tubes for rodents to kill ticks at their source, before migrating to humans and other hosts. The 4-Poster might be less desirable as CWD approaches the Eastern Metro area. For that reason, tick tubes might be the more preferred strategy until the DNR reduces the spread of CWD further south. Currently, there is no evidence of CWD spread into Washington County… yet.

Deer Feeding Ban

Native and local deer herds are receiving the blame for poor non-lethal management. Deer feeding attracts outside herds to move into areas while retaining local deer from what would otherwise participate in natural migratory behavior. Stevens Point, which also culls deer and has for 25 years, has similarly stated that they had problems with people feeding deer.

On March 17, 2021, Goebel stated that he “was not in the helicopter but gave instructions to use tally marks for every feeder but was told after that there were too many to count, that they are everywhere and it ranged from piles of several hundred pounds of corn on the ground to small feeders but it was very evident where the deer are feeding with cattle paths going through the deer feeders. We plan to get code enforcement involved.” Even more, Goebel said, “What was very surprising was all the deer feeders that were spotted, the council does want to do something about that in Mahtomedi, it is against state law, the DNR has banned deer feeding in Washington County as well as it violates our City Ordinance.”

Despite this, the city only had three enforcement calls in 2021, two of which were subject to verbal warnings the previous year. It seems the enthusiasm to quell this problem stopped once the meeting adjourned.

It does not look like the city is properly enforcing its own ordinances. How much do these numerous feeders contribute to what is perceived to be an overabundance of deer? Would the city have these issues with deer if it were to appropriately and more actively enforce the deer feeding ban?

Lethal Control

According to Dr. Uma Ramakrishnan of The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, “Intermediate to low levels of hunting may result in improved overall deer health and reproductive output, because hunting often reduces competition for the surviving deer, which then have access to more food, resulting in more fawns.” She also noted that hunting strategies may be ineffective because deer learn to avoid areas during periods of hunting. The Humane Society notes that killing programs “usually do not achieve the intended management goals.”

Additionally, taking does can actually lead to an increase in fawn production. A study by Charlie Killmaster, who later became Deer Project Leader for the Georgia DNR, found that deer fetuses per doe nearly doubled the rut after a deer harvest. Mahtomedi’s current deer management plan does not appear to selectively target does, as recommended. Rather, the data appears to show deer killed indiscriminately. Consequently, despite more deer being killed in 2021 (by both hunters and other causes), the deer population in 2022 is at its second highest in a decade. Projecting 25 years into the future, it is possible based on the example of Stevens Point that the city will still be relying on lethal control without seeing a significant impact.

Numerous studies and resources indicate that a strictly killing-only plan is ineffective at long-term management of deer populations. Unfortunately, that is what the City of Mahtomedi is currently implementing. In fact, when pressed for data that showed all other solutions to the deer population were researched outside of hunting, Goebel responded with, “None.”

To be fair, Scott Noland of the DNR did present the city with non-lethal strategies, so the city was aware of the need to utilize a combination of management strategies to be effective. By his own admission, the public works director, Bob Goebel, revealed what appeared to be a lack of interest in considering these other strategies. It is important to note that the city also has a deer feeding ban, and so does the county. However, these feeding bans are only effective when they are adequately enforced. Data does not show that this appears to be the case, as previously referenced.

For the record, allegedly my grandfather used to employ professional sharpshooters to selectively remove deer when he was mayor in the 1980s and 1990s. These were not volunteers who managed to obtain a “sharpshooter” proficiency through an organization’s own self-certification standards and without apparent city oversight–these were consummate professionals with the proper training. Professional sharpshooters often consist of police, conservation officers, or park rangers, not volunteers that hit a 4-inch target at 20 yards. It is important to note that volunteers are allowed to take proficiency tests once a day. No data was reported about the frequency of testing nor proficiency results for the contracted hunters.

Metro Bowhunters vs. Other Sharpshooting Alternatives

The only visible benefits to using MBRB over other solutions is the cost difference and, perceptively, that it provides convenient hunting opportunities to the group’s members. However, as literature has shown, lethal removal requires continual maintenance to be effective. Removal by lethal-only methods does not appear to be effective at long-term management.

One of the city’s resources was “Managing White-Tailed Deer in Suburban Environments,” which recommended the following for sharpshooting–none of which appear to be utilized by the bowhunters.

- The level of experience of the personnel involved and the program design should be thoroughly assessed.

- The city had no data demonstrating knowledge of the volunteer personnel involved prior to the hunt, outside of the group’s liaison. The city did not document the legal names of its volunteers for liability purposes. Rather, the city actively tried to find ways to keep that data from the public so they wouldn’t have to release it.

- The city had no data showing that background checks were performed on volunteers, whose services necessitated the use of dangerous weapons, as defined by Mahtomedi ordinances. Additionally, no data showed these individuals were subjected to mental health evaluations before their services were employed by the city. This is especially concerning because the city screened its fire department applicants after the killing of a local bar owner by a city employee with access to a deadly weapon. No such screening appears to have been used here.

- The city had no data demonstrating proficiency test results, exclusively trusting MBRB to oversee qualification standards and without requiring any documented proof of qualifications delivered to the city.

- The city never maintained or received hunt logs in 2020, despite this being a contractual requirement. The 2021 hunt log was created by city staff based on information provided verbally by MBRB, written down on post-it notes, and transferred onto a spreadsheet. It does not appear the city was ever in possession of the original hunt log.

- Metro Bowhunters has a mandatory reporting requirement for all shots taken. None of this data was ever provided to the city.

- There was no data that showed long-term projection and planning for deer management. There appears to be little coordination between the city and the county regarding long-term management strategies beyond the implementation of hunting. Data about dead deer was not always consistent with county police records. Also, there were discrepancies between the city and MBRB hunt data, which showed inconsistencies. No targets or limits were established in formal documents for 2021.

- Baits should be used to attract deer to designated areas.

- Metro Bowhunters forbids the use of any attractant scents.

- According to Noland, “Baiting only happens during the sharpshooting process.” This further distinguishes Metro Bowhunters’ process from recommended sharpshooting processes. Continued commentary during a public meeting with MBRB clarified that there is no baiting.

- When possible, select head (brain) or neck (spine) shots to ensure quick and humane death.

- Metro Bowhunters prohibits these types of shots, noting in their literature that these shots are “NOT TO BE ATTEMPTED AT ANY TIME.” These tend to be for a variety of reasons, involving safety and chance of wounding without killing, as bowhunting differs from typical sharpshooting. It must be stated that bowhunting as a removal method is not the most humane method of deer removal. Dan Christensen, former president of MBRB noted that archery kills by hemorrhage so the animal bleeds to death and that its death is not instantaneous, allowing deer to travel 150 yards of where they were struck.

- Process deer in a closed and sheltered facility.

- Contracted bowhunters were required to field dress deer on city property and remove them from the hunting area unless allowed by private landowners. No data was ever provided about the city’s designated areas. However, Oakdale was concerned about the “psychological impact” and those upset about seeing “dead deer being removed from the park.” Oakdale is currently proposing to keep deer management activities out of the nature preserve.

- Donate meat to food banks for distribution to needy people in the community.

- There is no government data showing any distribution of meat to food banks and shelters. City data only showed two interested residents who wanted the venison.

- According to The White-Tailed Deer Handbook: “One of the restrictions hunters must commonly accept are demonstrating public service by giving up the meat, hide, and antlers of any deer killed, and increase meat for welfare programs by donating all or part of any deer killed to charity.” This data should be tracked by local government units and the DNR to ensure, and to provide transparency to the public.

This same guide also noted less efficiency and lower success rates for bowhunters. However, examples for use of compound bows or crossbows with minimum peak draw weight of 50 pounds were recommended, citing close ranges of 10 to 15 yards while deer were feeding at bait piles.

Venison Donations

The city’s website listed that: “Deer harvested by the Metro Bowhunters Resource Base will be used by the hunters, donated to nearby residents who request it and given to area food shelves.” Christensen told residents that the hunters “certainly participate in venison donation programs.” However, the evidence from the hunt in Mahtomedi did not provide proof of this community service to the needy. The city of Stevens Point, Wisconsin has complete transparency with its residents for how many deer were culled, the gender of the deer, how many pounds of meat were processed, and how many people benefitted from the food pantry.

The city clerk noted that two residents received donated venison and that “the City does not have data on other donated venison.” The city attorney concurred, stating, “No data exists.” This is a glaring oversight by the city of Mahtomedi, considering over one-third of the city’s 2021 quality of life survey respondents reported being financially stressed.

It is also notable that Metro Bowhunters, the group contracted by the city of Mahtomedi, claimed that their activities were “recreational” and that their data should be classified as private. The city attorney disagreed, stating that: “The deer hunt is not administered by the City as [a] recreational or social program, but rather is a strategy adopted as part of the City’s Deer Management Program and implemented by a separate non-profit organization pursuant to a contract between the City and the non-profit organization.”

If these hunts are in fact recreational, and if the contracted hunters are utilizing the privilege of hunting in these residential areas as recreation, and provided the group wants to classify public data about its service as private and therefore inaccessible to the public, the city should charge a nominal fee for providing close, convenient, recreational opportunities within the community, consistent with city schedules for other such activities. This revenue could then be used by the city to invest in other combined mitigation measures.

However, if the volunteer hunters are being employed by the city to carry out deer management services, then the city should consider deer meat to be an in-kind contribution of goods for their service, and data should be maintained about where goods procured from the government are transferred. All donations of meat should be tracked so there are no questions about where these resources are going and whom these resources are benefitting. This method would provide the best amount of transparency to the public, and is highly recommended.

Data indicates that Mahtomedi does not currently go through a stricter permit process to allow hunting because the deer are taken during the open hunting season; the permit process requires the surrender of antler racks and donations of all meat to the needy. These requirements should also apply to all volunteers of city culling programs.

Migration Patterns

Dr. Ramakrishnan’s study found that: “Typically, suburban deer found in areas of very high deer density, have relatively small home ranges. The data revealed that most suburban female deer had very well-defined movement patterns – when moving from forested areas to feed in people’s back-yards, they typically chose specific gardens and went to the same locations on repeated nights.”

Relocation

Cost tends to be the first considered reason not to relocate deer. At approximately $1,000 per deer, relocation is not a typically palatable, cost-effective option. However, local volunteers can make this more manageable.

While my initial impression was that relocation could be a viable strategy to mitigate in areas of high deer population densities, this is not possible in Minnesota for several reasons. According to DNR Wildlife Supervisor Scott Noland, relocation is not allowed in the state and any trapped deer are “put down.” Captive deer transportation was banned by the DNR in an effort to combat the spread of chronic wasting disease. Trapping and relocating deer also results in high mortality rates for the animals due to capture myopathy and capture shock. Studies have shown up to 85% mortality rates within the first year after transport with 4% dying on the way. Penn State discussed deer relocation in more detail. Although well-intentioned, trapping and moving deer to other areas is really not the humane approach it sounds like.

This study on the effects of capture-related injury is an informative read.

Vehicle Collisions

Arguably, one of the most dangerous incentives to implementing lethal management strategies are wildlife-vehicle collisions. However, The Humane Society reported that studies have shown in some cases that reducing the deer population does not necessarily correlate with decreases in collisions with vehicles. In some areas, deer collisions with vehicles are higher in areas of low density populations.

Police records from July 2015 that spanned a two-and-a-half year period indicated that collisions were most frequent on Wildwood Road. This was followed by Hilton Trail/Highway 244 and Mahtomedi Avenue. These locations appear to be consistent with the city’s log of dead deer. These stretches of roads also tended to be the most highly ticketed for speeding and using electronic devices while driving, among other problems. The city’s 2021 city-wide survey also indicated 59% of respondents were concerned with traffic speeding, 50% concerned about pedestrian safety, and 48% concerned with bicyclist safety. Could deer collisions on these roads be better attributed to unsafe driving practices that need to be addressed by the community and local law enforcement?

More data on Minnesota deer-vehicle collisions can be seen here. It is important to note that in most cases, animal-vehicle collisions result in no human injuries.

It should be noted that deer are statistically most likely to cause accidents from October to early December and in the early morning hours and the evening during rut. In the spring, young deer are likely to find their way onto the highway as they seek new territories.

Wildlife Crossing Structures and Fencing

The Mahtomedi City Council’s goal with its deer management plan was “to create an acceptable environmental balance that will facilitate the peaceful co-existence of citizens and wildlife.” Yet, very little data demonstrates this commitment.

Enter wildlife crossing structures. The Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program devoted $350 million dollars in grants over five years to help make major roadways easier to cross for wildlife. and studies have shown these to reduce collisions by 80-90%. This concept builds bridges for native wildlife to provide safe passage for the animals while reducing the chances of accidents. These crossings are not just limited to extravagant multi-million dollar projects. Crossings could be as simple as installing underpasses to save turtles and other small animals from becoming roadkill. The only responsive data was from 2019, showing that there would be cutouts in the surmountable curb for turtle access in the area of Birchwood Road, and councilor Dick Brainerd’s suggestion to place signs to warn drivers about turtles crossing.

When asked about these mitigating measures, the Mahtomedi City Council failed to reply. The only response came from the city clerk, who said there was nothing in the minutes about it. This is an appalling oversight, as the Trunk Highway 244 has been completely closed while undergoing construction. This was an excellent time for the city to work with the county to implement wildlife crossing structures, especially given the federal subsidies that could help.

Additionally, strategically fencing off stretches of highway that are most likely to endanger motorists would help guide wildlife to safe locations where they will not be killed. One study showed that fencing alone reduced collisions by 87%. It does not appear that the city researched or looked into any of these options, according to documents obtained through an expansive data practices request to the city. The only consideration appears to be from Washington County, adding a natural-bottom culvert under 244 at Lost Lake. Additional documentation from Washington County showed that wildlife crossings for the 244 construction project had received interest during public comment and as noted on the overlap map. Despite this interest, no action was taken to put in these vital infrastructures.

Sterilization and Birth Control

The options for these appear limited at the current time. However, the costs of implementing surgical sterilization on the deer population appears to be a cost-effective median outside of using hunting. The plan for Clifton Heights not only humanely stabilized the deer population over the span of five years, Clifton Heights decreased the population to more manageable levels in a way that was lasting and sustainable. As with any initiative, startup costs were higher than other alternatives. However, with prolonged sustention of an effective program, long-term overall costs decrease.

Clifton Heights demonstrated community involvement, sending local residents who were interested to obtain training to dart deer. By utilizing volunteers in this capacity, Clifton Heights was able to bring down overall costs associated with sterilizing deer.

There are two main strategies for sterilization: those that target 80% of female does (requiring oophorectomies or tubal ligations) and those targeting 100% of the buck population for vasectomies. One promising technique that still leaves male sex organs intact is the scarring of the vas deferens, which promotes natural behaviors that removal testes would otherwise inhibit. Due to they polyamorous nature of male deer, I am curious about future studies that target both populations, allowing select specimens to stay fertile in the population for a stable regrowth.

At the current time, both immunocontraceptives are expensive and require revaccination. Such is the case with GonaCon. While effective at two doses, long-term financial viability of this method is not supported. PZP appears to be a more financially viable option, if birth control were to be utilized. Capturing, tagging, and dosing costs $500 per deer. However, darting is relatively inexpensive, around $100 per deer and demonstrates an 80-90% effectiveness rate.

It is my assumption based on the efficacy of these techniques and programs that willing field volunteers and veterinary volunteers might be able to substantially offset costs of using other population controls. In the long-term, sterilization is more cost effective than both sharpshooting and birth control individually. Based on the Clifton Heights model, a one-time tax increase of $30 per household would cover the costs associated with the first three years (and arguably the most expensive component) of their deer management program. Their program was able to obtain donations and grants to do the work, and is something that could feasibly be used in Mahtomedi’s case. Additionally, Clifton Heights offered an “Adopt A Deer” naming program to help offset costs and draw community engagement. All of these considerations would set Mahtomedi apart as an example of humane deer management, potentially making its name recognized for a follow-up study that further proves that humane deer management can be sustainable and work.

In calculating the costs of such mitigating measures, it is important to also consider all costs associated with population control, not just the primary cost of hunting, sterilizing, etc. What are the costs and losses of damage to landscaping? What are the ecological damages that will cost money in restoration efforts? Unfortunately, the city has tabulated little of this data beyond a few citizen complaints of damages and their assertions of cost. All of this data should be maintained to understand the scope of the problem and the full cost-benefit analysis of any such population control strategy.

Deer Crossing Signs, Other Electronic Mitigation

MNDOT has ceased replacing deer crossing signs, citing research that shows the signs are ineffective at reducing collisions. This appears to be, in part, because drivers quickly grow accustomed to those signs. Although, some research refutes this. Interestingly enough, it also seems like Washington County is currently implementing turtle crossing signs (I have asked for the research to support this paradox). Also, reduced speed signs have not been found effective for reducing collisions because motorists do not obey the signs. Here again, it seems that human behavior is at the root of hindering effective deer management. So what can be done?

Regarding speed limits, strengthening local enforcement campaigns is a good start. Although stationary signs have not been effective, moveable and changeable message boards have shown statistically significant reductions in collision rates. When implementing a changeable message sign (CMS), the Virginia Transportation Research Council saw a 51% decrease in collisions. There is a limited body of research on these sorts of advisory warning signs and other dynamic signage. Some evidence suggests motion sensors–whether it be to detect deer or to show messages when cars are closer–might help as well. Low-cost, seasonal, stationary signs have shown 26% reductions in collisions. Others have shown 51% reductions that taper down over time. Some suggestions indicate that moving signage to strategic locations or only showing messages at certain hours might reduce accidents. There are also other more costly solutions using digital motion sensors and lights to alert drivers of wildlife presence.

Clearing vegetation from the sides of the road have also shown small, but improved reductions in collisions (20% and 38%).

Park Remaining Closed to the Public

Mahtomedi closed Katherine Abbott Park to the public during hunt dates. While this gives the appearance of “safety,” it also disadvantages tax-paying members of the public who routinely use the parks system–especially those who have interest in using the park and disagree with the hunts entirely (again, only an approximated 22.5% strongly favored the hunts to begin with). Goebel told the city council in October 2021, prior to the hunts, that there would be two hunters in each location. In reality, seven hunters were frequently present in Katherina Abbott Park.

This is where Mahtomedi should look to neighboring communities, if it chooses to continue these practices. According to John Moriarty of the Three Rivers Parks District: “While we used to close parks completely for archery hunts, we now leave them open with appropriate signage alerting guests to the hunt. This change occurred after park users requested access to the parks during archery hunts. In recent years, we left a few trails open, and the results were extremely successful. Because of the thorough orientation process and fact that archers pre-select their stand sites, park visitors were able to safely use the parks with no negative interactions with hunters.”

Did Mahtomedi consider fair treatment of park users when they passed their deer management resolution? Would the whole park have needed to be closed if Goebel stuck to his word and only placed two hunters in each zone?

Conflicts of Interest

This section is not meant to detract from the beneficial aspects that the DNR covers and actively contributes to the preservation of our natural resources. Rather, this is meant to demonstrate how conflicts of interest or perceived conflicts of interest within subdivisions of government might skew the tides of deer management.

One of the DNR’s expressed purposes is to provide hunting and fishing opportunities. The DNR actively seeks to recruit and retain hunters and anglers, especially trying to impart these values to those of different cultural backgrounds. “This will be a recruitment challenge because some of these populations do not have the cultural references or tradition-based experiences that would exert internal pressures to pass these activities on to the next generation… Government and stakeholder organizations need to better understand and adapt to the race/ethnicity challenge.” This would seem a rather ethnocentric goal, especially to populations that might not want to carry on these Minnesota traditions. Especially in light of recent media attention on empowering cultural minorities in an area traditionally strong in European cultural norms, are the DNR’s goals in these regards culturally insensitive? Its literature’s wording strongly denotes that races and ethnicities whose cultural references do not support hunting are a “challenge.” A challenge to whom: earlier immigrant cultures who might be facing a shift in populations with similar values and mindsets, or the DNR’s bottom line?

Revenue is a major factor for scrutiny. The DNR receives revenue through hunting and fishing licenses. In 2004-2005, this appeared to have comprised roughly 22% of the DNR’s annual funding sources. According to one article, deer licenses provide over $20 million in annual revenue to the DNR and “tens of millions more in ancillary purchases by hunters.” The DNR’s Deer Management Account “rebounded with increased hunting opportunities (increased bonus permit sales) and the increased allocation of adult deer license sales revenue to this account.” Coincidentally, Metro Bowhunters states on its website: “You need to have at least one bonus tag in your possession.” The DNR report continued to detail: “Based on the 2011 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation, the total annual economic impact of hunting in Minnesota exceeded $725 million and more than 85% of hunters in Minnesota hunt deer.“ Could the decision to allow hunting in residential areas be strongly influenced by DNR revenue?

Many of the members on oversight committees appear to be hunters. In fact, current MBRB president Deb Luzinski sat on the Wildlife Oversight Committee (WOC) from 2011 to 2014, according to the Liaison to GFF Oversight Committees. Luzinski was “a member of the Board nearly as long as MBRB has been in existence” and also was in the role of vice president by as late as 2014.

Isn’t this a conflict of interest?

According to the oversight committee’s charter:

A volunteer activity under the direct supervision of the Fish and Wildlife Division and/or associated with activity within the scope of the budgetary oversight review could be perceived as a conflict of interest. The appointee should choose a volunteer activity with that in mind and maintain a “clean separation” to avoid the appearance of a potential conflict.

Metro Bowhunters could directly benefit from the way this oversight committee spent money on wildlife management. Most certainly, given the close relationship between MBRB and the DNR, it gives the appearance of a potential conflict of interest. According to 2022-2023 eligibility requirements: “Persons whose employment may involve administration of activities funded by the Game and Fish Fund are not eligible for appointment. Examples of such activities are land acquisition; land and water management; fisheries and wildlife management; pass-through funding for such activities; state lottery; and similar activities related to management of fish, wildlife and habitat.” Given this current eligibility requirement, it might be implied that prior appointment might have been unethical, or at the very least, risking the perception of an ethical oversight committee.